Why AI Needs Human-in-the-Loop Systems

Summary

AI systems excel at speed and pattern recognition but struggle with hallucinations, bias, edge cases, and explainability. Human-in-the-loop (HITL) design embeds human judgment into critical decisions, improving accountability, fairness, and resilience. By combining machine efficiency with human context and ethics, organizations build AI systems that are more trustworthy, adaptive, and effective over time.

Key insights:

Hallucination Risks: AI can produce confident but incorrect outputs, requiring human validation in critical use cases.

Edge Case Detection: Humans identify distribution shifts and novel scenarios where AI performance weakens.

Ethical Judgment: Value-based trade-offs and fairness concerns demand human reasoning and oversight.

Clear Accountability: HITL preserves legal and organizational responsibility for high-stakes outcomes.

Trust Calibration: Human review fosters appropriate trust without encouraging blind reliance on AI.

Continuous Improvement: Human feedback generates high-quality data that strengthens models over time.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence has made significant progress. Large language models can write code, and computer vision systems can diagnose diseases with accuracy rivaling medical specialists. Autonomous systems can navigate complex environments and make split-second decisions. Yet, despite these impressive capabilities, the most successful AI deployments share a common characteristic: they incorporate meaningful human involvement at critical junctures.

This creates an interesting paradox. We build AI systems to augment human effort, yet the most reliable and trustworthy applications are those that explicitly design humans into the loop. This is not a failure of AI technology; it represents a mature understanding that AI and humans excel at different things. While AI systems process vast amounts of data and identify hidden patterns, humans provide contextual understanding, ethical reasoning, and the ability to navigate ambiguity. The goal is not to choose between AI and human intelligence, but to design systems that leverage the strengths of both.

The Technical Imperative: Understanding AI Limitations

Hallucinations and Confabulation

Hallucination is one of the most significant challenges in deploying AI systems. When models generate outputs that appear credible but are factually incorrect or entirely fabricated. This is not a bug that can be patched; it is an inherent characteristic of how current AI systems, particularly large language models, function.

Language models are trained to make predictions based on patterns in their training data. They do not possess an internal model of truth or reality; they prioritize likelihood based on statistical correlations. When asked about topics outside their training distribution or when synthesizing information across multiple domains, these systems can confidently generate information that seems authoritative but is completely incorrect.

Consider a medical diagnosis system that uses AI to interpret radiology images. The AI might identify a shadow as potentially cancerous based on visual patterns. However, without human oversight, the system cannot account for the patient's medical history, recent procedures, or imaging artifacts that a radiologist would immediately recognize. A HITL system allows the AI to flag potential concerns while ensuring that a qualified medical professional makes the final diagnostic determination, considering the full clinical context.

Edge Cases and Distribution Shift

AI systems perform best on data similar to what they were trained on. However, the real world is full of edge cases that don't neatly fit established patterns. When AI systems encounter these situations, their performance can degrade dramatically, often in ways that are not immediately obvious.

A content moderation system trained on English-language social media might struggle with regional dialects and code-switching between languages. An autonomous vehicle trained primarily in sunny weather might behave unpredictably during its first encounter with heavy snow. A fraud detection system optimized for typical transaction patterns might fail to recognize novel fraud schemes.

This is where the role of human operators in HITL systems comes into play; they can recognize when an AI system is operating outside its area of competence and intervene accordingly. More importantly, their feedback on edge cases becomes valuable training data that helps improve the system over time, gradually expanding its capability to handle unusual scenarios autonomously.

Opacity and Explainability

AI systems, particularly deep neural networks, operate as 'black boxes.' While we can observe their inputs and outputs, understanding the internal reasoning that led to a particular decision can be extremely difficult or impossible. This opacity becomes problematic in situations where understanding why a decision was made is as important as the decision itself.

In regulated sectors like finance, healthcare, and criminal justice, explainability is often a legal necessity. A loan rejection must come with a clear explanation. A medical treatment recommendation needs to be justified to both patients and regulators. Criminal risk assessments used in sentencing decisions must be transparent and defensible.

HITL systems address this challenge by ensuring that decisions attributed to AI systems actually involve human judgment and can be explained in human terms. The human expert reviews this information, applies domain knowledge and contextual understanding, and makes the final decision that they can then explain and defend.

The Ethical Imperative: Responsibility and Fairness

Bias Amplification and Discrimination

AI systems learn from data, and if that data reflects historical biases, the AI will learn to perpetuate and potentially amplify those biases. Numerous domains have experienced such biases: discrimination against women by hiring algorithms, poor performance of facial recognition on darker skin tones, and credit scoring systems that disadvantage minority communities.

Biased AI systems often appear objective. AI can create an illusion of neutrality, making discriminatory outcomes seem like inevitable mathematical conclusions. With HITL systems, it’s easy to identify and mitigate bias. Human reviewers can review AI recommendations for patterns of discrimination, challenge decisions that seem unfair, and provide corrective feedback.

Accountability and Legal Liability

Someone must be accountable for the outcomes of consequential decisions made by AI systems. If an autonomous vehicle causes an accident, who is responsible: the manufacturer, the software developer, the owner, or the AI itself? If a medical AI system misdiagnoses a patient, who bears liability?

Present legal frameworks are built on the assumption of human decision-making and responsibility. Establishing clear accountability chains remains challenging, though the law to address AI systems is still evolving. HITL systems provide a straightforward solution: by ensuring that humans make or approve critical decisions, they maintain traditional accountability structures while still leveraging AI capabilities.

This is not just about assigning blame when things go wrong. Clear accountability encourages responsible development and deployment of AI systems. When developers know that humans will review AI recommendations and be accountable for final decisions, it creates incentives for building systems that are transparent, reliable, and worthy of trust.

Value Alignment and Ethical Reasoning

Many important decisions involve ethical considerations that cannot be reduced to optimization metrics. Should an autonomous vehicle prioritize passenger safety over pedestrian safety? How should a medical AI system balance life extension with quality of life? What privacy invasions are acceptable in the name of security? These questions involve values, trade-offs, and contextual judgment that current AI systems cannot navigate independently.

Stakeholders may have different legitimate but conflicting values. Different cultures prioritize different ethical principles. Contexts change what ethical course of action is appropriate. The complexity and context-dependence of real-world ethical reasoning ultimately require human judgment when trying to encode ethical principles into AI systems.

HITL systems allow AI to handle routine decisions that are ethically straightforward while escalating complex ethical dilemmas to human decision-makers. This ensures that value judgments reflect human values, are made by entities capable of ethical reasoning, and can be adjusted as societal values evolve.

The Practical Imperative: Building Trust and Improving Performance

User Trust and Adoption

For AI systems to be effective, users must trust them sufficiently to rely on their outputs and recommendations. However, blind trust in AI is dangerous, while complete distrust makes AI systems useless. The goal is to build appropriate trust. Users should understand the strengths and weaknesses of AI systems.

When users know that AI recommendations will be reviewed by qualified human experts, they can trust the overall system while maintaining healthy skepticism about AI components. This is particularly important for novel AI applications where users don't yet have experience to calibrate their trust appropriately.

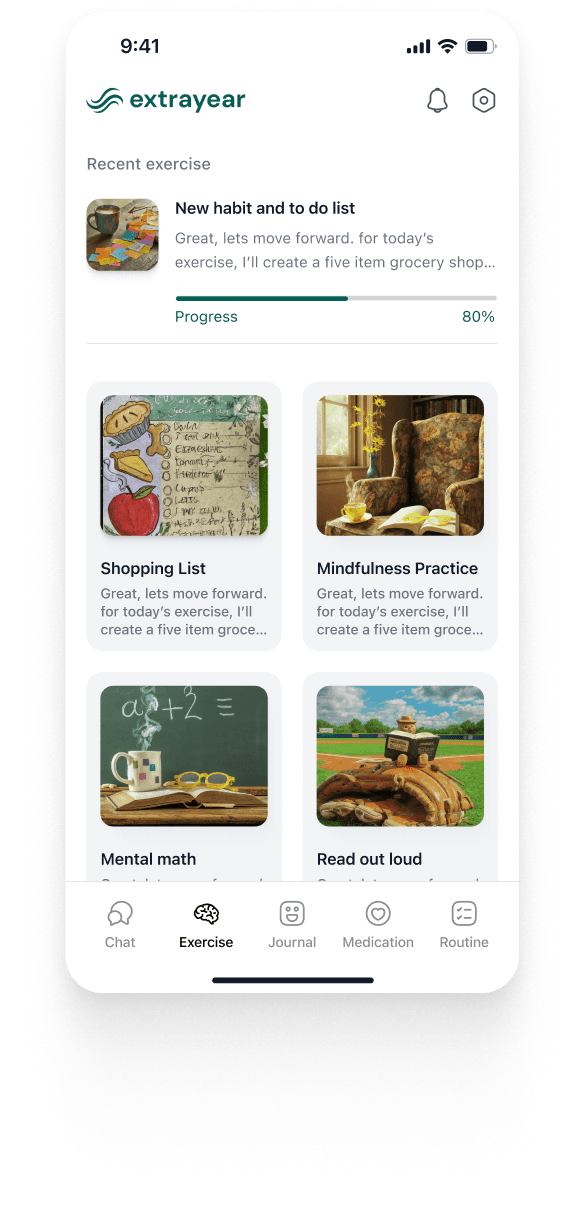

Consider automated customer service. Pure chatbots often frustrate users when they can't handle complex requests or understand nuanced problems. But a HITL system that seamlessly escalates complex issues to human agents while handling routine queries automatically provides a better user experience and builds trust. Users learn they can rely on the system for simple tasks while knowing that human help is available for harder problems.

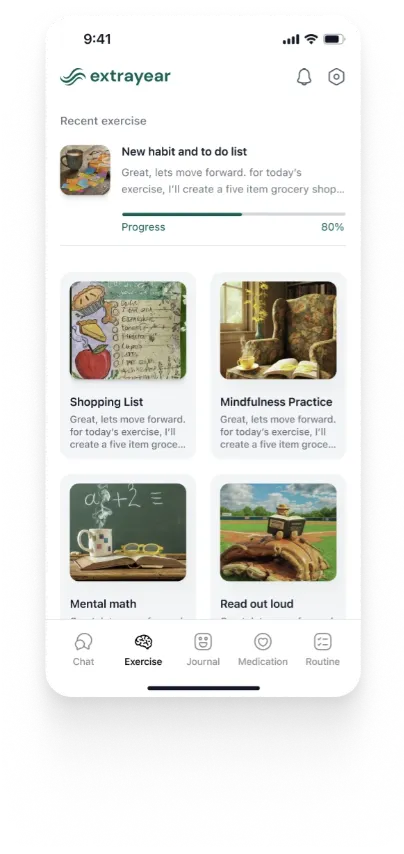

Continuous Improvement Through Active Learning

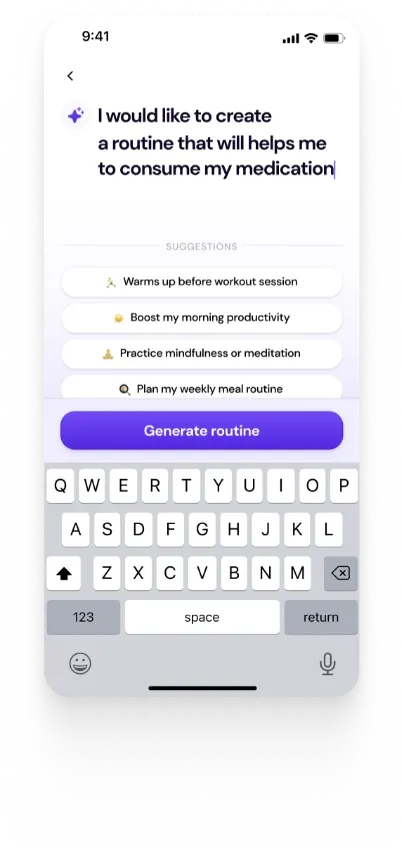

One of the most powerful advantages of HITL systems is their ability to continuously improve AI performance through active learning. When human operators review AI decisions, especially cases where they disagree with AI recommendations, they generate high-quality labeled data that can be fed back into training pipelines.

This creates a virtuous cycle: AI makes predictions, humans review them and provide corrections, these corrections become training data, and the improved AI makes better predictions. Over time, the system becomes more accurate and requires less human intervention. The AI gradually takes on more responsibility as it demonstrates competence, while difficult or ambiguous cases continue to receive human attention.

This is particularly valuable for addressing edge cases and distribution shifts. As the system encounters new scenarios that the AI handles poorly, human corrections teach the AI how to handle similar cases in the future. The system's capabilities expand organically based on real-world needs rather than trying to anticipate every possible scenario during initial development.

Graceful Degradation and Fail-Safes

Even well-designed AI systems will occasionally fail. The question is not whether failures will occur, but how the system responds when they do. HITL systems provide natural fail-safes by ensuring that human judgment can override AI recommendations when something seems wrong.

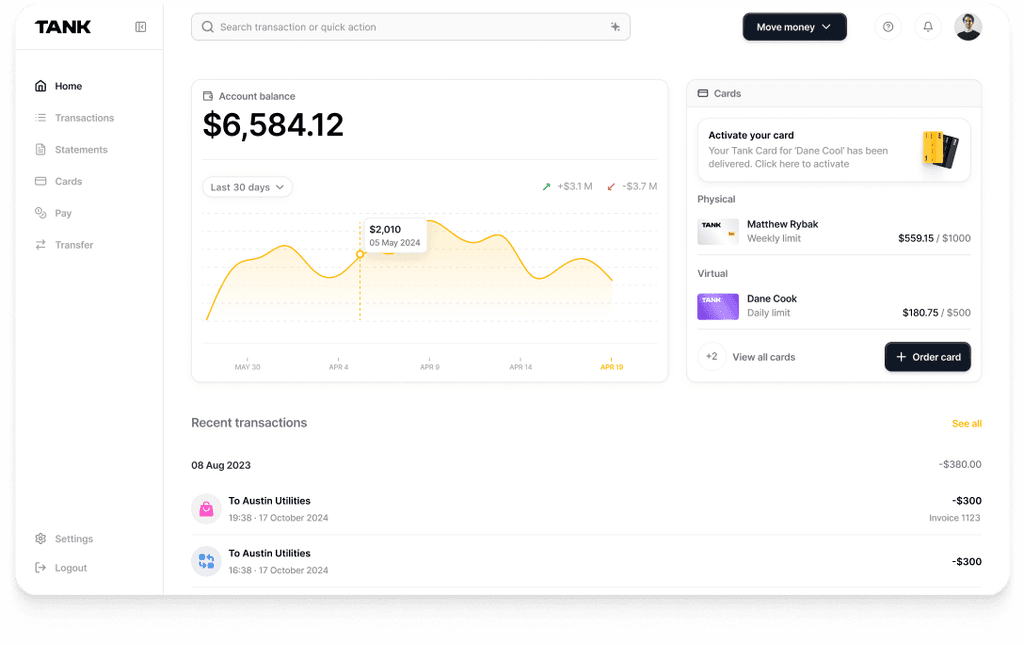

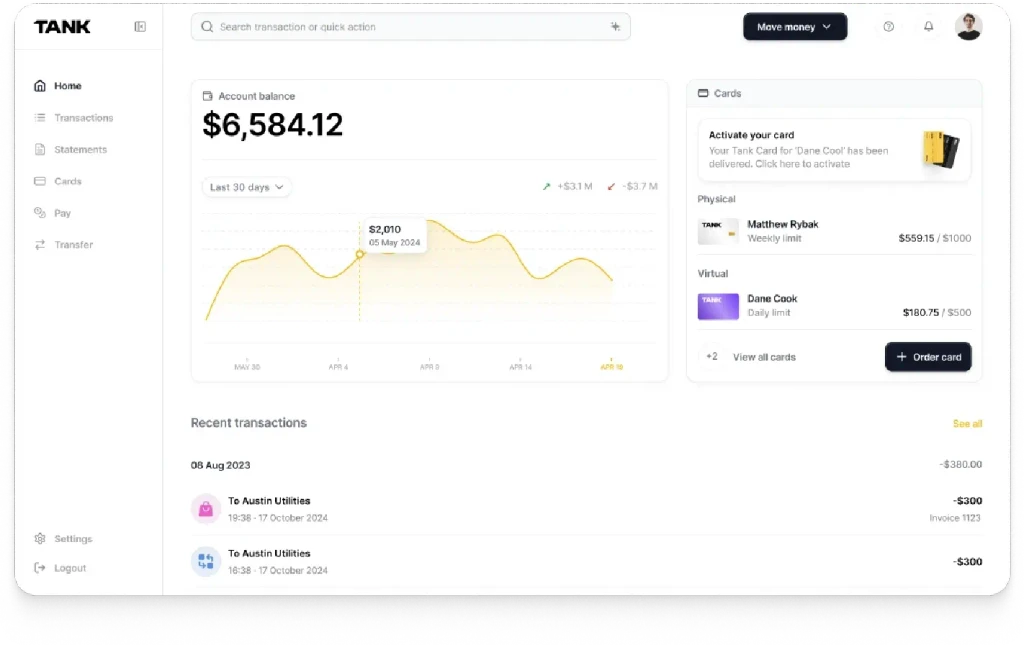

Consider a trading algorithm that detects an unusual market pattern and recommends a large trade. In a fully automated system, this trade might execute before anyone realizes the AI has misinterpreted data or encountered a bug. In an HITL system, a human trader reviews large or unusual trades before execution. If the recommendation seems off, they can investigate further or override the AI. This prevents catastrophic failures while allowing the AI to operate autonomously in normal circumstances.

HITL systems also support graceful degradation when AI components fail. If an AI service goes down or produces obviously incorrect outputs, human operators can temporarily take over critical functions until the issue is resolved. This resilience is crucial for systems where continuous operation is essential.

Implementing Effective HITL Systems

Design Patterns and Intervention Points

Effective HITL systems require thoughtful design to balance automation efficiency with appropriate human oversight. The key is identifying optimal intervention points, when and how humans should be involved in the AI decision-making process. Several common patterns have emerged:

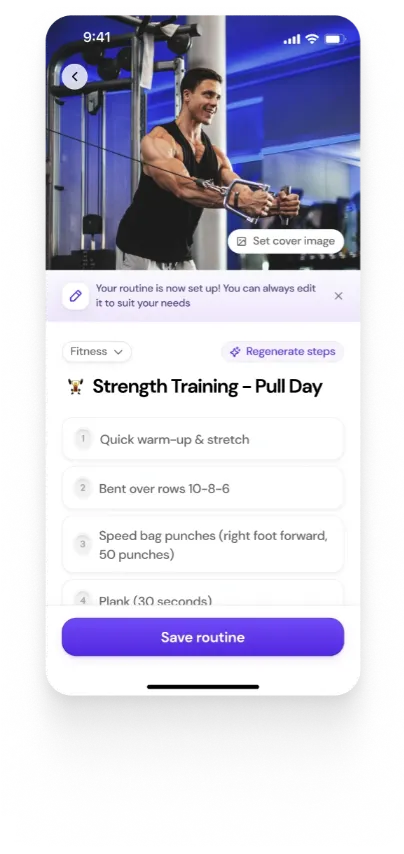

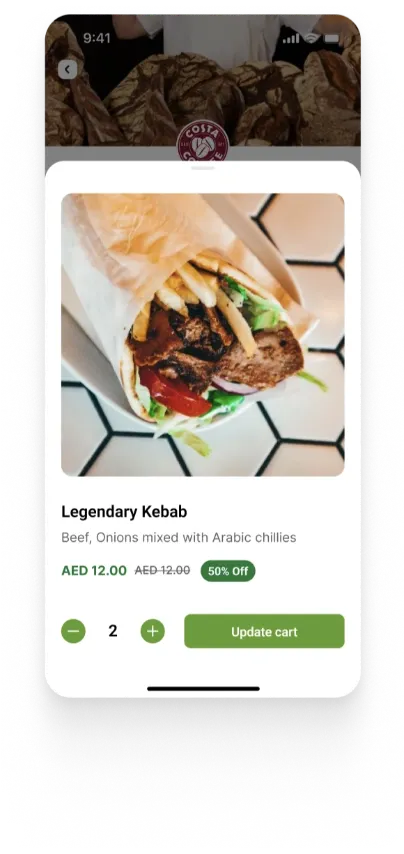

Review and Approval: The AI makes recommendations, but humans review and approve them before implementation. This is common in content moderation, where AI flags potentially problematic content and human moderators make final decisions about removal.

Confidence-Based Escalation: The AI handles cases where it has high confidence in its predictions, but escalates ambiguous or low-confidence cases to human review. For example, automated document processing might extract clear fields automatically but flag unclear handwriting for human verification.

Exception Handling: The AI operates autonomously within defined parameters, but alerts humans when it encounters exceptions or unusual situations. Autonomous vehicles, for instance, may operate normally in most conditions but request remote assistance when facing novel scenarios.

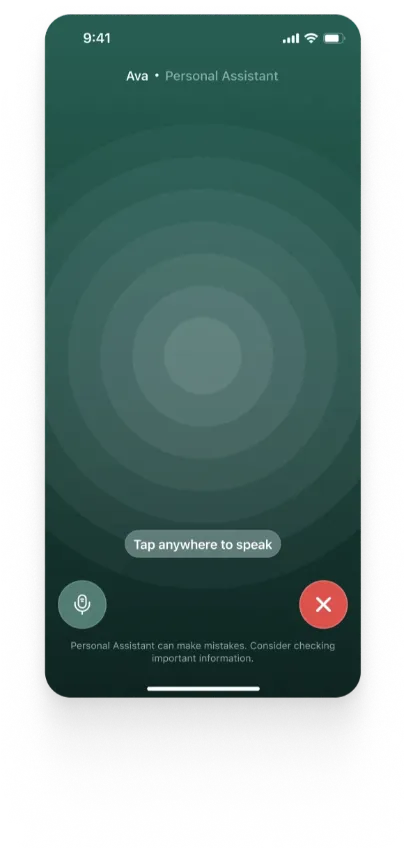

Human-AI Collaboration: Rather than sequential review, humans and AI work together on tasks, with each contributing their strengths. A doctor might use AI analysis to identify potential diagnoses while applying clinical judgment and patient interaction to reach a final conclusion.

Periodic Auditing: For high-volume, low-stakes decisions, AI may operate largely autonomously with periodic human audits to verify quality and identify systematic issues. This is common in email spam filtering, where most decisions are automated but samples are reviewed to ensure accuracy.

Interface Design and Decision Support

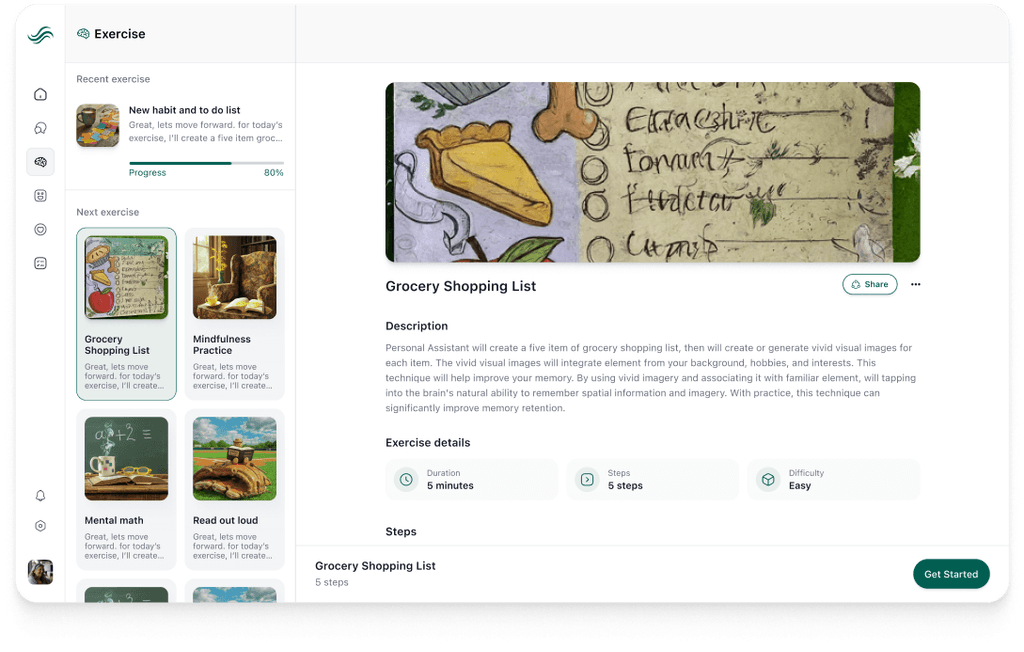

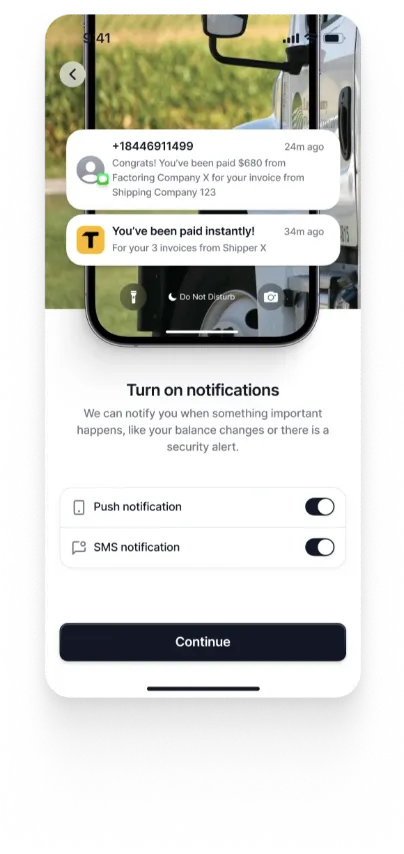

The effectiveness of HITL systems depends heavily on interface design. Human operators need clear, actionable information to make informed decisions quickly. Poor interfaces can become bottlenecks that negate the efficiency benefits of AI automation or lead to errors where humans rubber-stamp AI recommendations without proper review.

Effective HITL interfaces should clearly present AI confidence levels, provide relevant context and supporting information, highlight why the AI made a particular recommendation, flag potential issues or edge cases, and make it easy for humans to accept, reject, or modify AI suggestions. They should also support efficient workflow, recognizing that human operators may be reviewing many cases.

Importantly, interfaces should be designed to maintain human attention and critical thinking rather than encouraging complacency. Research shows that when AI systems are usually correct, human operators can become overly reliant on them and stop carefully reviewing recommendations. Good interface design includes features that promote active engagement, such as requiring operators to justify decisions or periodically presenting test cases with known correct answers.

Feedback Loops and Model Improvement

To realize the full benefits of HITL systems, organizations must establish robust feedback loops that capture human decisions and use them to improve AI models. This requires infrastructure for collecting human corrections, systems for validating and cleaning feedback data, pipelines for retraining models with new data, and processes for evaluating and deploying improved models.

However, naive approaches to learning from human feedback can introduce problems. If the AI only learns from cases humans reviewed, it may become overfit to difficult or edge cases while forgetting how to handle routine scenarios. If feedback is inconsistent because different human operators have different judgments, the AI may learn confused patterns. Careful design of feedback collection and training procedures is essential to avoid these pitfalls.

Active learning techniques can help optimize which cases are sent for human review. Rather than random sampling or only reviewing cases where the AI is uncertain, systems can strategically select cases that would be most informative for improving the model. This maximizes learning value from limited human review capacity.

The Future: Evolving Human-AI Collaboration

As AI capabilities advance, the nature of human-in-the-loop systems will continue to evolve. We can anticipate several trends that will shape future HITL implementations.

Dynamic Autonomy Adjustment

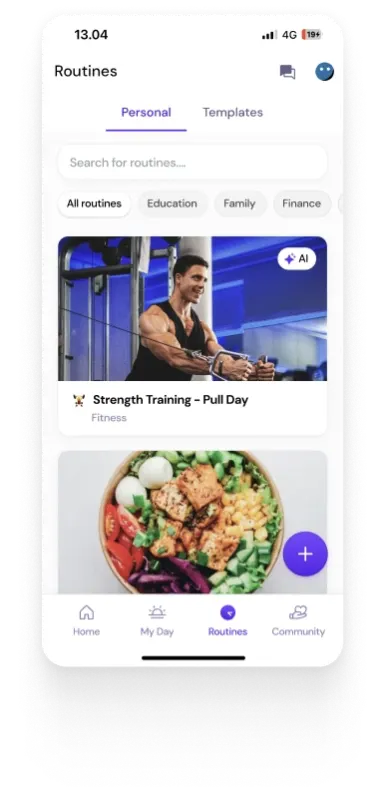

Future HITL systems will likely feature dynamic adjustment of autonomy levels based on demonstrated performance and context. Rather than static rules about when humans are involved, systems will continuously evaluate AI confidence and accuracy, automatically adjusting how much human oversight is required. When AI performance is strong and stakes are lower, the system operates more autonomously. When uncertainty is high or consequences are significant, human involvement increases.

This adaptive approach maximizes efficiency while maintaining appropriate safety margins. It also allows AI systems to gradually take on more responsibility as they demonstrate competence, rather than requiring upfront decisions about autonomy levels that may become overly conservative or dangerously permissive as capabilities evolve.

Augmented Intelligence Rather Than Artificial Intelligence

The distinction between AI automation and human-in-the-loop systems may blur as we move toward genuine augmented intelligence, systems designed from the ground up to amplify human capabilities rather than replace them. Instead of asking "what can AI do autonomously?" we should ask "how can AI and humans work together to achieve outcomes neither could accomplish alone?"

This shift in perspective leads to different system architectures. Rather than building AI systems that occasionally need human input, we would build collaborative systems where human intelligence and machine intelligence are tightly integrated from the start. The goal becomes enhancing human decision-making and productivity rather than automating humans out of the loop.

Specialized Expertise and Distributed Review

As AI systems become more sophisticated and specialized, HITL systems will likely involve different types of human expertise at different stages. Rather than a single human reviewer, complex decisions might involve input from multiple specialists. AI might handle initial processing, domain experts might review technical aspects, ethicists might evaluate value trade-offs, and affected stakeholders might provide input on potential impacts.

This distributed review model acknowledges that no single human has all the expertise needed to fully evaluate complex AI-assisted decisions. It also creates checks and balances, reducing the risk that AI recommendations are uncritically accepted due to automation bias or deference to authority.

Regulatory Frameworks and Standards

As AI systems become more prevalent in critical applications, we will likely see increased regulatory requirements for human oversight. Regulations may mandate HITL systems for high-stakes decisions, specify minimum qualifications for human reviewers, require documentation of human review processes, or establish standards for interface design and decision support.

Industry standards and best practices for HITL implementation will also mature. We will develop better frameworks for determining appropriate levels of human involvement, validated interface designs that promote effective human oversight, established metrics for evaluating HITL system performance, and shared approaches to feedback collection and model improvement.

Conclusion

AI and human intelligence are complementary, not interchangeable. AI thrives on scale, speed, and consistency, while humans bring context, ethics, creativity, and adaptability. Human-in-the-loop (HITL) systems are not a stopgap until full automation, but a deliberate design choice that ensures accountability, trust, and continuous improvement. Success lies in organizations that build synergy between humans and machines; through thoughtful interfaces, feedback loops, and organizational processes. As AI advances, the nature of human involvement will evolve, but human wisdom and values will remain essential. The future of AI is collaboration, not substitution.

References

Amershi, S., Weld, D., Vorvoreanu, M., Fourney, A., Nushi, B., Collisson, P., Suh, J., Iqbal, S., Bennett, P. N., Inkpen, K., Teevan, J., Kikin-Gil, R., & Horvitz, E. (2019). Guidelines for Human-AI Interaction. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300233

Cai, C. J., Jongejan, J., & Holbrook, J. (2019). The effects of example-based explanations in a machine learning interface. Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, 258–262. https://doi.org/10.1145/3301275.3302289

Holstein, K., Vaughan, J. W., Daumé, H., Dudik, M., & Wallach, H. (2019). Improving Fairness in Machine Learning Systems. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300830

Mosqueira-Rey, E., Hernández-Pereira, E., Alonso-Ríos, D., Bobes-Bascarán, J., & Fernández-Leal, Á. (2022). Human-in-the-loop machine learning: a state of the art. Artificial Intelligence Review, 56(4), 3005–3054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10246-w

Shneiderman, B. (2020). Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence: Reliable, Safe & Trustworthy. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(6), 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1741118

Wang, D., Weisz, J. D., Muller, M., Ram, P., Geyer, W., Dugan, C., Tausczik, Y., Samulowitz, H., & Gray, A. (2019). Human-AI Collaboration in Data Science. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359313